Fedpunk – the DHS and you

You can do what’s right, or you can do what you are told.

Phil Ochs

It was a rage that pressed itself against my face, hot to the touch. I sat in the van and cried, nothing but pressure under my eyes. Snot plugged up my nose as I tried to control my breathing while I leaned back in the front seat. It was the most mad I had ever been in my life, and it remains the maddest I’ve ever been. This kind of anger can’t be accessed in response to an individual. This kind of anger is only set upon by a system. Unmatched in its consequences, a failing system is massive, completely all encompassing, and crushing to bore alone: It’s government work.

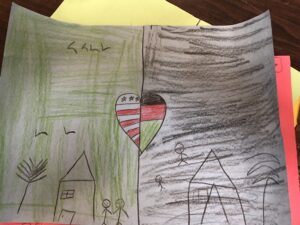

Involvement defined by chaos and empty commitments, Afghanistan was left behind along with its inhabitants. Throughout the west’s history of involving ourselves in the secluded mountain nation, from the British India company to the Soviets, in each engagement it can be clearly pointed out the parties involved had no interest in understanding the nation. Afghanistan has been treated as means to an end, with her people secondary to what we needed from their land strategically. Afghanistan is a nation of warriors, built out of Jihad. Fiercely defensive and unconquered for thousands of years, independence was unquestionable. The only people able to conquer it are other Afghans. Anybody watching the news could’ve seen the photos taken of this populace pouring over themselves on the tarmac runways to desperately try and escape the inevitable takeover of the Taliban. This was who operation allies welcome was for. In a humanitarian initiative to pick up the pieces of this 20 year failure, we evacuated the huddled masses into military bases across the country as resettlement agencies scrambled to catch up with our decisions.

Desperate for support, the department of homeland security pooled together a misshapen group of active military, a variety of agencies, and small private organizations in order to care for the new 70 thousand strong influx of people. Being in one of the agencies called upon for support, Americorps NCCC, I had the unique opportunity of being a barely graduating burnout tasked with teaching English and providing care to a group of refugees whose language I did not speak and who’s entire culture or history I knew little about. The prospect of the entire operation stunned me, the option of failure looming across all my aspirations to lift up a people fucked over. Initially told very little about practical involvement, we spent time while traveling to the base in order to prepare ourselves to understand a group Americans traditionally have little contact with or understanding about. Homeland security provided quick sensitivity training packets to print out on our own, basics about culture that the average American wouldn’t know. Eye contact was to be avoided, and children were not to be touched. Strict guidelines for how we were to interact with them and where were set up, creating a very natural border against us.

The WW2 era barracks people had been placed into were long white rectangular buildings, 2 stories tall with red slanted roofs. Connected by metal stairs at the backs as fire escapes, kids hung swings in these made out of leftover sheets. Rows of beds equally spaced themselves along the halls, but the barracks dedicated to the Afghan people stood converted into a more personable living space, becoming a shanty town of cloth. The colorful floral patterns from donated blankets divided the open floors into rooms to give modicums of privacy. While never allowed inside the actual residential buildings, passing by at the strict 15 MPH limit enforced by MPs gave me ample time to gaze across the rows of halls from behind the windows that they called home. Cloth divided halls contained their own fractured family units in a bazaar of blood, each its own inaccessible world.

This DIY ramshackle approach to life is omnipresent in a “refugee camp”, even one built with such powerful forces swinging their weight behind it. One of these resources was an emergency respite center, emergency childcare or shelter for anybody who needed it for any reason. This could be as simple as their parents having a baby and having to go to a hospital for a while, or it could end up being a shelter for domestic violence victims. This is where I worked for a couple days. It was basic childcare, keeping kids entertained while they stayed for as long as they needed to stay. We had access to a translator, a volunteer from Afghanistan who spoke English, Pashto and Dari. Long days of kicking balloons and watching all the kids’ content we could find in Dari eventually fractured into planning periods of figuring out how to jam as much education and enrichment as possible into the days that we had them. Anything responded to with learning retention or excitement, what’s what we did. Providing a resource like this was incredibly important, and keeping it open was even more valuable. Striking to me was the memory In between groups of kids. Members of my team and I worked on curriculum exercises while alone in the center, generally quiet only interrupted by passing conversation from the soldiers standing guard at the desk. Any break in this was out of the ordinary, and any would-be visitors were shooed away to preserve it as a safe space. The only people in and out were homeland security or children.

As such, it was surprising when a woman clad in hijab entered, escorted by soldiers. With a covered face it was difficult to make out anything, but a huddled position and urgent hushed whispering coloured the meeting important. From the translator’s low tones, all I could make out from the situation was that she needed help for her and her kids. Protection from her husband. However, here’s an intake process to do anything on base, and it means you get the pleasure of paperwork. As the conversation went on, she began to become increasingly upset. She had no desire to write her name attached anywhere, a paper trail was risky for her and her kids. Despite being reassured that this information was only available to us, she wouldn’t budge. Without a signature or data entry, there would be no assistance. I heard our bosses argue to theirs that she’s afraid, and by not accepting her we would put her in danger. The chilling response to this was that if she was in danger, she would sign it to keep her family safe, and that this was a final decision; ending the conflict completely. We didn’t dare speak up at the moment, and I’m ashamed of myself. Not because it would’ve changed her situation, nothing would get her into the safety of the center save for her signature, I stayed in the barracks and had no money to offer her. But my boss’s boss needed somebody to be fucking mad at them without a shield of polite office jargon to shield them. An actual fuck you, she needs help. I didn’t do it.

The respite center sat empty for days, whether this was through no need for it or because nobody knew to go. We were sent away to merge into the rest of our group and help out in different facilities and programs. While the rest of the group worked mostly as teachers aides, helping with pronunciation and spelling, the other facility provided was a recreation center. I decided I would work full time there as a point of contact, and try to lead our efforts there. Throughout the months working there I cycled through 3 bosses, each worse then the predecessor for various reasons. At first everybody involved was inexperienced and slowly figuring out systems to set up with consistency. Our games included pushing the kids across the linoleum as fast as we could on leftover office chairs, office chair soccer, and office chair jousting. As we added more supplies and shifted gears towards also providing activities such as concerts, Job fairs, and movie nights, we were able to take community engagement and feedback to figure out what people hated and loved. Soccer was popular, we kept an entire section of the warehouse off for soccer. Cornhole was unpopular, so we got rid of it. Our systems developed as we learned what the people liked, and we began to fall into a rhythm of what we set up. Our art corner came along. There was a small bowling lane, a circle with smaller toys confined within a circle of chairs to prevent any theft, the tricycles, things that were used got put out.

The first transfer of bosses was relatively uneventful. She seemed nice enough, and wanted to provide the best service she could just like any of us. Her issue came simply down to presence. As we ran the center as we had been for a few weeks, any managerial need dissolved. As such, She was relatively absent from large portions of the day. Enough so that many volunteers who weren’t as full time as me didn’t particularly know who she was. It wasn’t particularly disastrous, save for the moments where we waited for her to show up with the keys outside the building as she ran late. At this point the Afghan people who ran the concerts and sound systems knew exactly what they were doing. We understood the projector, we could set everything up ourselves and it was fine. Kids could run around, play, and do their thing; for the most part it could be called an organized chaos. The most grievous injury that occurred was a kid with a basketball throwing it downwards, looking downwards, and having it bounce up and hit him in the face causing him to lose a tooth. As time went on we even got military personnel placed on site to help out, which ranged from group to group on how useful they were. Sometimes they would sit in the corner and play on their phones as we ran around, Sometimes they would make real genuine efforts to interact with the kids. They would play together, really try to be a friendly face in a new country that can be pretty scary a lot of the time; beyond this, they helped us out so much. Usually the number ratios were absolutely stunning, we could have up to 80 kids at one time and only have 5 volunteers working. When they helped it was lifesaving. For the life of me I don’t understand why that wasn’t something that the groups of soldiers stationed could volunteer for; If they want to be there and help, that’s who we want.

Towards the end of my project there was a final staff changing, which wasn’t anything new. Consistency wasn’t ever provided in staffing, the DHS switched hats and chairs frequently, on seemingly esoteric decisions. Our new boss really didn’t like children. Or at least, these kids. The first change instated was we were to carry a bottle of sanitiser on us, as the kids were dirty. We were to wipe down the surfaces they touch, and not physically interact with them anymore. At the time I was exhausted, working 12 hour days 6 days a week, and naively charitable as my job position really didn’t allow me to get into challenges with anybody above me, so I brushed this off as covid safe policy. Later, in a particularly late night after closing, it was really apparent what she meant. She talked about how shockingly disgusting the kids from afghanistan were, when she was stationed there herself. How they didn’t understand brushing their teeth or wearing shoes, how backwards their nation’s sense of self was. We needed to be providing classes to teach them this kind of thing. She warned male soldiers to not ever be an a room alone with the women from afghanistan as they would accuse them of rape in an attempt to get a green card, and trap them in a marriage. Abjectly horrifying. Being privy to this, I finally had some form of courage and went to my boss in my own program to file a complaint in any official capacity. I knew examples of people higher up that cared, that wanted good for people; there had to be recourse. I just had to ride out my last few weeks under her, stick my nose down, and keep working with the kids to get them what they wanted from us. Soon after, I came into new set-ups. Now our group was to set up tables in an L shape across the warehouse. Educational flashcards on stations were set up, Math and English dominating most of them. Kids were no longer allowed to be running or yelling, we were more scholarly now. While I’m not opposed to education, my problem came in here: there was no need. The Afghan people themselves had already created a curriculum based schooling system on their own. That’s what the rest of my team did full time, work in the classes with the teachers who create an educational environment. This went on for a couple days, and I watched as the kids I had developed informal relationships with, played with, and got to really know despite not speaking the same language disappear. For the first time in my employment I spoke up.

I told her that we were not an authority over the kids and cannot force them to go to our schools, and that those who chose not to go to school deserved a place to safely play inside from the winter. I told her our attendance had more than halved, that we weren’t giving them what they wanted. I was only told we were given them what they needed, and I was to go get my boss to speak with her. I love my boss dearly. She is an absolutely wonderful person, who didn’t have as much of an opportunity as us to work in as many classes while she was busy managing shuttling us around for our complex schedules. Without her our group’s involvement would have been absolutely impossible. She also was beholden to the government, as was I. I would have to formally apologize to this fucking woman. All I could do was go sit inside the van and make sure I didn’t sob in front of her, calming myself down. In essence all I was able to say was “I apologize for my unprofessional behavior and disrespect.” She had me hug her, and I did. It was neutering, but any chance of working in this sector in the future depended on this. Going back to my barracks I began to wonder about if I could even go into the government after this. Despite the image of somebody who worked for the department of homeland security, I’d always been vaguely to some nondescript position on the mid-far left, using this as a vehicle to do good. Detangling myself from the machine left me exhausted in my last week. Sitting in the van to pick up coworkers for dinner at the barracks, we watched as some teenagers ran around the snow covered base in an intense fight. Without thinking, I’m outside in my fleece jacket, balling up snow in my clammy hands. Sprinting around the grounds, an afghan snowball fight is serious shit. They pack like they’re from the midwest, and aim for the head. I remember sprinting away from a group of kids as they chased me down, before falling and slamming down onto the ground. Within seconds, hard packed near ice was hitting against me, scrambling to escape. Crawling away until I hit the wall, I remember seeing 5 kids lined up with snowballs in their hands. I curled up on the wall, and laughed as they aimed for the head.

These kinds of experiences coloured the base’s bureaucratic humanitarianism. I think I did good work. I’d hope that some of the kids remembered me in a positive light and that I helped bring structure to chaos. I don’t think I’ll stop working in government, soon I’m heading off to the environmental sector which has its own slew of problems. But in working with the beast, You’ll see the mechanics of it. How it chews up people. It’s disturbing. I think you can be true to your overall values and hold a job like this, even if it destroys bits of your conscience. But you have to hold your consciousness to remember that, and it’s truly damaging. I’m still tearing up about this. I never know if the last person who ran the recreation center ever got fired. All I know is that when I left the base I sobbed into my pillow in the van, thinking about how I needed to stay. Every single one of those people from Afghanistan were failed by a system, and I was part of it.

I hope I can be forgiven at some point.